dieser beitrag wurde verfasst in: englisch (eng/en)

Lucienne Bloch (1909–1999), Swiss-american muralist, painter, printmaker, photographer, and educator

By Alex Winiger

Geneva (Switzerland) born Lucienne Bloch migrated to the USA in 1917. She is best known for her photograph portraits of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, and for her WPA mural for the Womens' House of Detention in New York City (1936). As a muralist and educator, and together with her husband Stephen Pope Dimitroff (1910–1996), she handed down fresco technique in the USA as far as to the 1990s.

[Click into the images to enlarge.]

Origins, migration, education

Lucienne Bloch was the third child of the musician, composer and educator Ernest Bloch (1880–1959). Her father, offspring of a jewish family in Geneva, had set his course early in his life towards a musical career, with little success in Europe. An engagement led him to USA in 1916. He soon found support and success there, and his family moved to the US in 1917.1 After attending Hathaway Brown School for Girls in Cleveland, Ohio, Lucienne entered The Cleveland Institute of Art instead of high school. In 1925 she was able to change to the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, into the class of Antoine Bourdelle (1861–1929). Complementary to this, she started to study with André Lhote (1885–1962), a non-academic teacher. In 1927, she had her first contact with traditional muralism, in the shape of Fra Angelico's paintings in Florence. In the same year, her father bought her a Leica camera.2

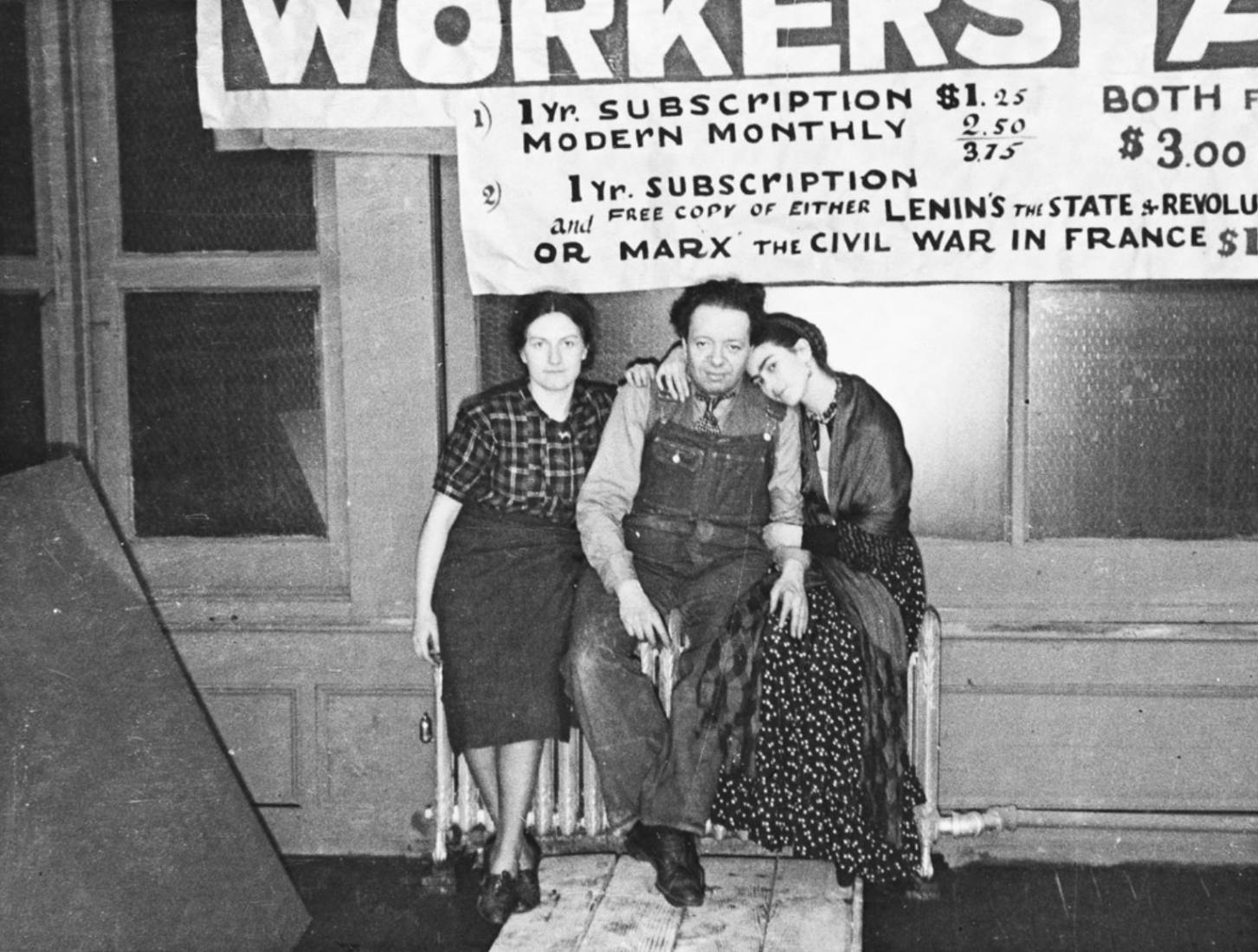

An acquaintance of her father, Petrus Marinus Cochius (1874–1938), a glass manufacturer in the Netherlands, opened the first paid job as a glass designer to Lucienne. She stayed in Leerdam from 1929 to 1931, when she was called by Frank Lloyd Wright to teach sculpture in Taliesin. Arriving in New York in 1931, she practised and published her photography, and exhibited her glass work. At a banquet she met the person who would give her further artistic life a new direction: the mexican muralist Diego Rivera (1886–1957), who had been commissioned several large murals in San Francisco and now in Detroit. On the spot he engaged her to assist him in the preparation of his forthcoming fresco exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art.3 On the way to her intended job in Taliesin, Lucienne joined Rivera in Detroit, where she assisted him in his work in the Art Institute and became a close friend of Frida Kahlo, which resulted in a travel to Mexico and many portrait photographs of Frida by Lucienne. In Fridas home, Lucienne met Frida's father Guillermo Kahlo (1871–1941), a professional photographer, and had the opportunity to exchange experiences with him.

The stage in Wisconsin turned out to be a short episode. Lucienne Bloch got aware that the school of Wright was to be established yet, probably a fine place for a fully formed artist's personality, but not for her who needed to create yet her own work. She therefore decided to return to New York.

Love and first success

In 1933, Rivera sent two of his Detroit assistants to prepare the wall for his work «Man at the Crossroads» in the Rockefeller Center in New York, today known for one of Rivera's fiercest confrontations, and the reason of the cancellation of further promised commissions in the USA. The young craftsmen contacted Bloch for financial support, which she conceded under the condition of being involved in the project as an official photographer. This is the reason that she became the author of the only existing photographs of the Rockefeller mural destroyed shortly afterwards.

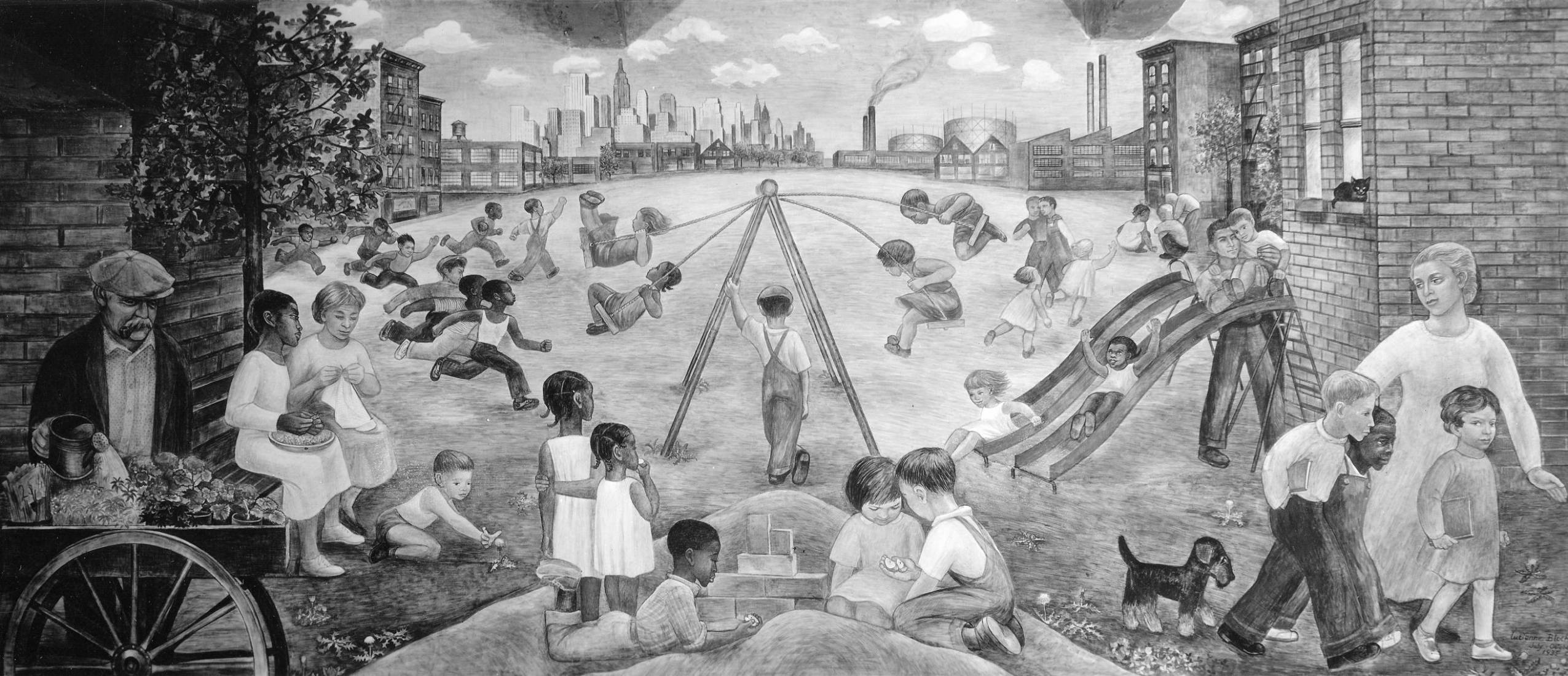

The longlasting consequence of this coincidence was that her meeting Stephen Pope Dimitroff resulted in love, lifelong partnership, and collaboration. In 1936 the two married. Already in 1934 they created a mural in a settlement house in the East Village. Lucienne Bloch enrolled for FAP-support and was commissioned to realize a large mural for a women's detention house on Greenwich Avenue, which was well discussed in the press, among others by Anita Brenner (1905–1974), one of the prominent promoters of mexican art in the USA. About in 1939, Bloch and Dimitroff moved to Flint, Michigan, with their new born son (whose godmother was Frida Kahlo), where Stephen Dimitroff worked in the automobile industry, while Lucienne Bloch created another two murals, for a school and a children's home. In the one for YWCA she extended her technical range towards casein color applied directly on bricks.4

Life and work centered in California

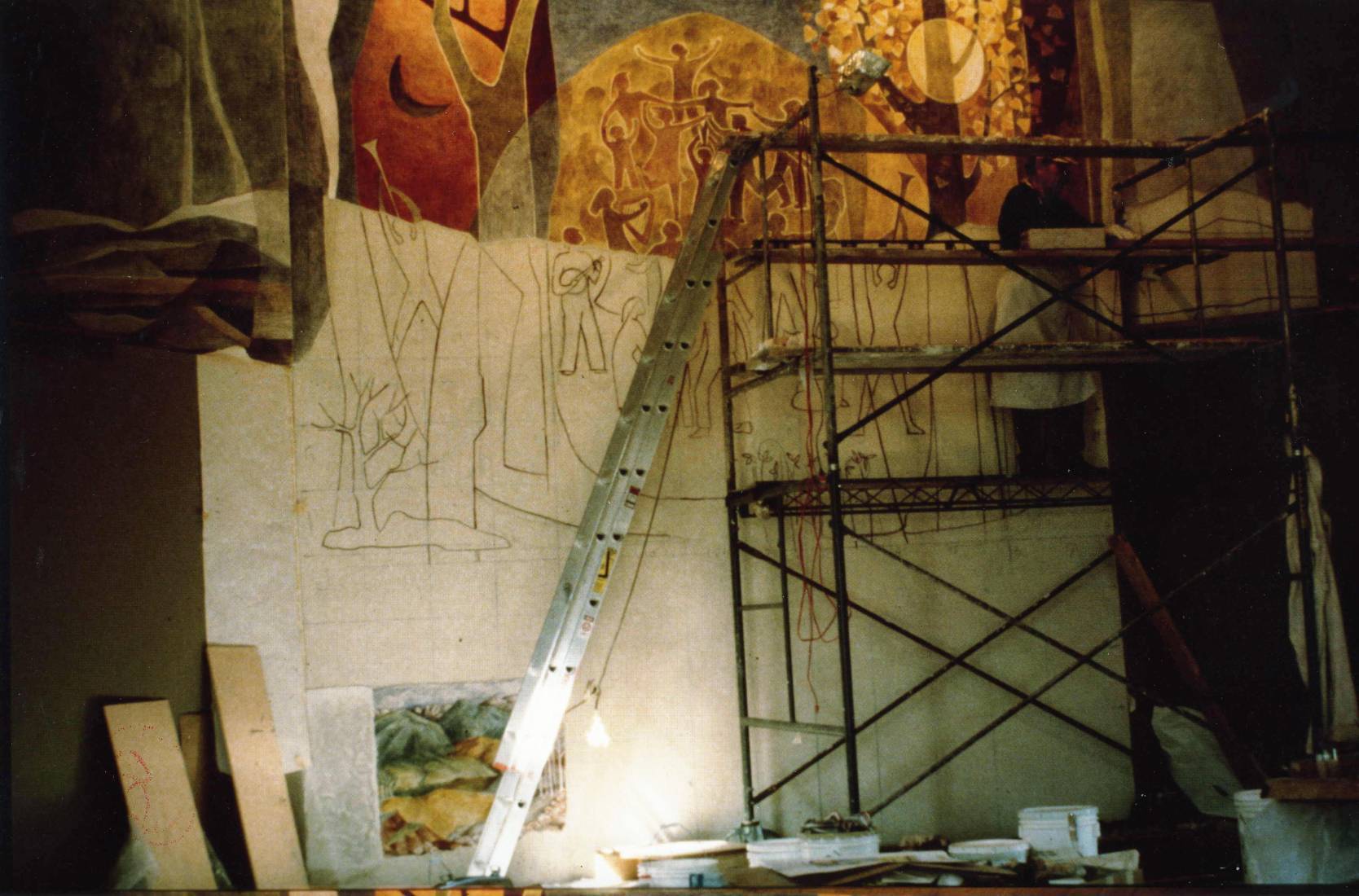

In 1948 the family, now grown to five members, moved to Mill Valley, California, and then, 15 years later to Gualala in Mendocino County. Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Dimitroff (usually as her technical supporter) left their mark on many walls of the region, but also on some in the east of USA. In 1958 they conceived a 17000 sqft. tile mural for IBM in San José. Prominent cycles were realized by them for the San Francisco National Bank in 1962 and 1963, as well as for the Calvary Presbyterian Church in San Francisco (1963) or the First Presbyterian Church in San Rafael (completed in 1974). Their technical range extended into mosaics and tile murals, but also acrylics. They created a large overall mosaic decoration for the Greek Orthodox Church of Oakland. In Erich Mendelssohn's Temple Emanuel in Grand Rapids, they applied oil and gold leaf. Fresco as they had learned it with Rivera, remained their unique proposition, the craft that they disseminated in their teaching and their murals.

Relevance and contextualization

When Lucienne Bloch started her career as a muralist, she used an straight, objective expression with social aspiration. Her work in the Detention House in Greenwich Village weighs as an independant, but not atypical work of the WPA/FAP-era. The most atypical aspect is that it is one of the rather rare female muralists who executed this complex and masterly work, and that she developed her career in the male dominated field of muralism with the help of her husband and not the other way round. Maybe more typical is that she was restricted to realize just one painting of a whole cycle of five paintings she proposed. Exceptional artists like Bloch or Marion Greenwood were allowed to execute a very limited number of paintings for the FAP. One can imagine what they would have created with the conditions that were offered to Greenwood in Morelia, or with the oppurtunity Thomas Hart Benton could realize a cycle in the New School in New York.

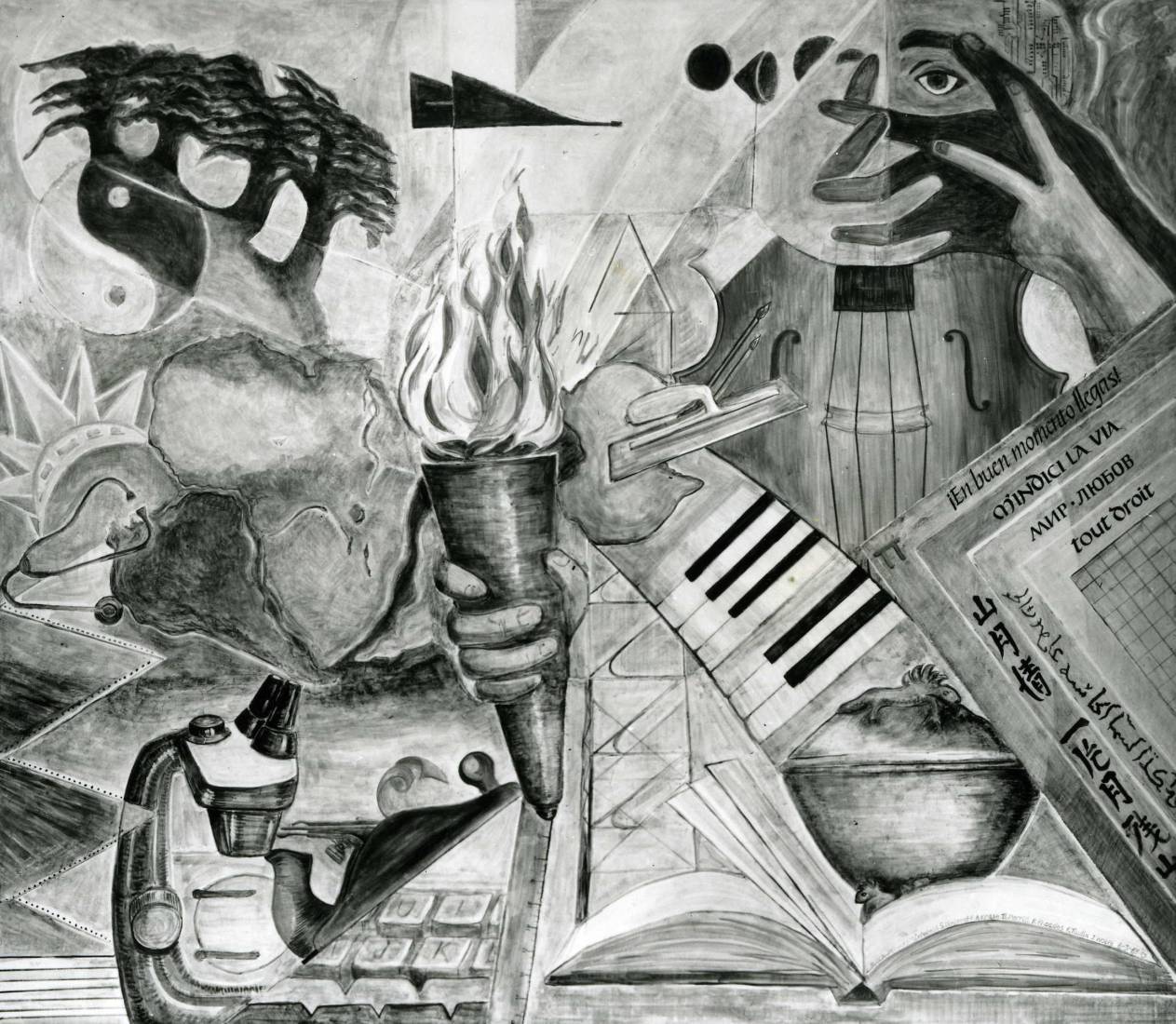

It is atypical as well that Bloch did not leave figuration after 1945 like many of her colleagues. In her «Evolution of Music» she introduced abstract elements which represent music as such. This had it's counterparts in some public works by New Yorkers of the time for broadcast studios where abstract paintings on that subject had been realized by Stuart Davis, Byron Browne, Louis Schanker and others.5 In her afterwar-works sometimes the decorative elements came to the fore, as can be seen in her Sanctuary Wall of 1953 in Grand Rapids. On the other hand, Bloch used a narrative, almost naive pictorial language, which starts with her Children's Home painting in Flint (1946) and reappears in many school decorations, masterly and complex in her late work «The Web of Life» in Fort Bragg (1987/88).

The working methods, the networks and the radiance of Lucienne Bloch have yet to be researched and told, including her work as a sculptor, plastic designer, printer, and educator. As mentioned, her activity did not end before the 1990s. It will be exciting to know whom she initiated into fresco technique or visual arts in general.

What happened to female muralists in Switzerland?

Is Lucienne Bloch's life conceivable under the condition that she would never have left Switzerland? This leads to the question if there were swiss women with a comparable career in her era. A few artists can be considered for a comparison, in a limited way. Marguerite Frey-Surbek (1886–1981), painter and muralist, from Delémont, living in Bern, married to the painter Victor Surbek (1885–1975), a successful muralist as well. Marguerite Frey learned in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière of Marta Stettler (1870–1945), a hotspot of avant-garde in Paris, around 1910. With her husband she founded a school in Bern which developed to a fermenting pot of modernists in a conservative setting. Unlike Bloch Marguerite Frey-Surbek, although socially very committed, focused on scenery painting. Her murals were pleasing, illustrative works. And although, related to swiss conditions, she is valued as a emancipated female artist, especially her public works were strongly overshadowed by the works of her husband. With Bloch she has in common that her activity protruded far into the postmodernist era – that she linked early twentieth century avant-garde with the post-1968 generation.

Female swiss artists of Bloch's proper generation who were active in the field of architecture related art often dealt with a traditional female dominated craft: textile. This is true for the german born Lissy Funk (1909–2005), and also for Bertha Tappolet (1897–1974) and Louise Meyer-Strasser (1894–1974) who led together an workshop for decorative arts («kunstgewerbliches Atelier») in the pre-war and war years, in Zurich. The contents of the works of these artists were conventional: (exotic) animals or the seasons for schools, the muses, the Evangelists, floral motives. Most important: their contribution to the national exhibition in Zurich 1939. Louise Meyer-Strasser's and Bertha Tappolet's work in the «Pavilion of the Swiss Woman» wore the french title «Nous voulons servir notre pays», which demonstrates the enourmous social pressure on public art of the time in general and the subordination of the women in particular. Nevertheless these women opened the field of public art to their gender partners of the next generation who established their position starting in the 1950s, and specially in the era after 1968.

Notes

- 1 Joseph Zemp, «Ernest Bloch, un compositeur suisse à la conquête du monde», on: ResMusica, August 17, 2023, https://www.resmusica.com/2023/08/17/ernest-bloch-un-compositeur-suisse-a-la-conquete-du-monde/ (accessed May 25, 2024).

- 2 Lucienne Allen, Old Stage Studios. The Artwork of Lucienne Bloch. Biographies, http://lucienne.readyhosting.com/biographies/lucienne_bloch.htm (accessed May 25, 2024). Many biographical details in the following stem from this web archive of Lucienne Allen, Gualala, and are partly based on oral accounts of her grandparents Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Dimitroff.

- 3 Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1152? (accessed May 25, 2024).

- 4 A collection of the mural works by Lucienne Bloch are noted on inventory lists created by Sita Milchev, her daughter, and by Lucienne Allen, her granddaughter. These works are now recorded in mural.ch.

- 5 See Jody Patterson, Modernism for the masses. Painters, politics, and public murals in 1930s New York, New Haven : Yale University Press 2020.

Literature

- Anita Brenner, «Muralist Lucienne Bloch – Product of the WPA», in: Brooklyn Eagle, Feb. 2, 1936, 12–13C.

- Mary Fuller, Robert McChesney, «Oral history interview with Lucienne Bloch, 1964 August 11», on: Archives of American Art, New Deal and the Arts Project.

- Helen A. Harrison and Karal Ann Marling, 7 American Women: The Depression Decade, Poughkeepsie, NY 1976.

- Francis V. O'Connor, WPA. Art for the Millions. Essays from the 1930s by artists and administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project, Greenwich CT 1976.

- Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, American Women Artists: from early Indian times to the present, Boston 1982.

- Suzanne B. Riess, Renaissance of Religious Art and Architecture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1946–1968. Volume II. Robert Olwell, Lucienne Bloch Dimitroff and Stephen Dimitroff, Mark Adams, Victor Ries, Ruth Levi Eis, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1985.

- Michele Vishny, «The New York City Murals», in: Woman's Art Journal , Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1992), pp. 23–28.

- Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., «Lucienne Bloch, Muralist, Is Dead at 90», in: The New York Times, March 28, 1999.

- Therese Bhattacharya-Stettler and Steffan Biffiger, Marguerite Frey-Surbek & Victor Surbek. 'Als Künstler sind wir nicht verheiratet', Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess 2018

- Kathleen Murphy Skolnyk, «Women of Art Deco», in: Art Deco New York journal, Vol. 5, Issue 1, Spring 2020.

- Barbara Haskell (ed.), Vida Americana. Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Caleb Wiseblood, «Ann Foxworthy Gallery curates new exhibit compiled from late artist Lucienne Bloch's personal archives», in: Santa Maria Sun, October 20, 2021.

- Elizabeth Frasco, «Walls Call: Women Artists of the NYC WPA in Mexico, 1929–1936», Woman's Art Journal 43(2), Nov. 2022, pp. 3–16.

Citation

Alex Winiger, Lucienne Bloch (1909–1999), Swiss-american muralist, painter, printmaker, photographer, and educator, Zurich 2024, https://www.mural.ch/index.php?kat_id=t&id2=87.